Chapter 5: Laplace Transforms notes, Kohler & Johnson 2e

5.1 Introduction to Laplace Transforms

The Laplace Transform

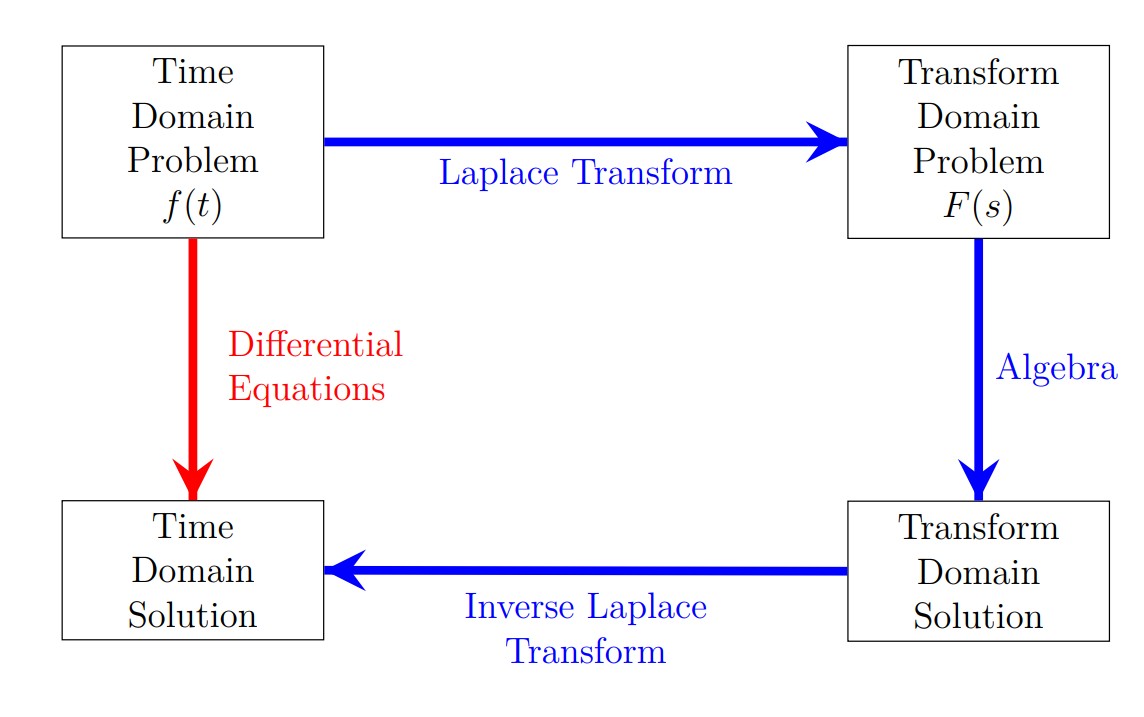

When we are looking at problems involving Laplace Transforms there are always 2 domains to which you need to pay attention:

- The time domain: variable (\(t\))

- The transform domain: variable (\(s\))

When you work problems you must be either entirely in the time domain or the transform domain. As a general rule you DO NOT work in both domains at the same time.

This flow chart shows the two different ways to solve a differential equation. You can either take the direct route or you can take the Laplace Transform route.

All Laplace transform problems have 3 steps:

- Laplace transform to make the problem algebraic (simpler).

- Solve/simplify the transformed problem with algebra.

- Inverse Laplace transform to find solution.

Solution: Recall the definition of an improper integral. If \(g\) is integrable over the interval \([a,T]\) for every \(T>a\), then the improper integral of \(g\) over \([a,\infty)\) is defined as:

\[\int^\infty_a g(t)\,dt=\lim_{T\to\infty}\int^T_a g(t)\,dt \tag{5.2}\]

We say that the improper integral converges if the limit in (5.2) exists; otherwise, we say that the improper integral diverges or does not exist. So when we integrate for a Laplace transform we use the limit definition of the improper integral.

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L} \{8 \} & = \int_0^\infty 8 e^{-st} dt\\ & = \lim_{T \rightarrow \infty} \left( \frac{-1}{s} \right) \left[ 8e^{-st} \right]_0^T\\ & = \lim_{T \rightarrow \infty} \left( \frac{-1}{s} \right) \left[ 8e^{-sT} - 8 \right]\\ & = \begin{cases} \frac{8}{s} & \text{for } s>0 \\ \infty & \text{for } s<0 \end{cases} \end{align*}\]

Notice that if \(s<0\) then \(e^{-sT}\) has a positive exponent and \(\lim_{T \rightarrow \infty}e^{-sT} = \infty\)

So we have found the Laplace transform of \(f(t) = 8\):

\[\boxed{\mathcal{L} \{8 \} = \frac{8}{s} \quad \text{for } s>0}\]

Note: Rather than using the limit for the improper integral we will realize that we are taking the limit but we will instead simply write:

\[\int_0^\infty 8 e^{-st} dt = \left( \frac{-1}{s} \right) \left[ 8e^{-st} \right]_0^\infty\]

Solution: This integral will require integration by parts twice. We can also look it up on a table of integrals:

\[\int t^n e^{at} dt = \frac{t^ne^{at}}{a} - \frac{n}{a}\int t^{n-1} e^{at} dt\]

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L} \{t^2 \} & = \int_0^\infty t^2 e^{-st} dt\\ & = \left[-\frac{t^2e^{-st}}{s} - \frac{2te^{-st}}{s^2} - \frac{2e^{-st}}{s^3} \right]_0^\infty\\ & = \left[ \left( -\frac{t^2}{s}-\frac{2t}{s^2}-\frac{2}{s^3} \right) e^{-s (\infty)} +\frac{2}{s^3} \right]\\ & = \begin{cases} \frac{2}{s^3} & \text{for } s>0 \\ \infty & \text{for } s<0 \end{cases} \end{align*}\]

\[\boxed{\mathcal{L} \{t^2 \} = \frac{2}{s^3}, \quad \text{for } s>0}\]

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L} \{e^{t^2} \} & = \int_0^\infty e^{t^2} e^{-st} dt\\ & = \int_0^\infty e^{t^2-st} dt\\ & = \int_0^\infty e^{t(t-s)} dt \end{align*}\]

This integral will always diverge because, for any \(s>0\) the exponent \(t(t-s)\) is positive for \(t>s\). This means that the Laplace Transform of \(f(t) = e^{t^2}\) DOES NOT EXIST.

Existence of the Laplace Transform

For a Laplace transform of a function \(f(t)\) to exist two things are required:

- The function must be piecewise continuous:

- Has a finite number of discontinuities on every finite interval.

- The limit from the left and the limit from the right exist at all discontinuities.

- The function must be exponentially bounded: There are constants \(M\) and \(a\) with \(M \geq 0\), such that: \[|f(t)| <Me^{at}, \qquad 0 \leq t < \infty\]

Laplace Rules:

The Laplace transform is a linear operator: Suppose \(f(t) = C_1 f_1(t) + C_2 f_2(t)\) \[\mathcal{L} \{f(t)\} = C_1\mathcal{L} \{ f_1(t)\} + C_2 \mathcal{L} \{f_2(t)\}\]

If \(f(t) = f_1(t) f_2(t)\) then \(\mathcal{L}\{f(t)\}\) exists.

The Inverse Laplace Transform and Uniqueness

They both have the same Laplace transform: \(\mathcal{L}\{f_1(t)\}=\mathcal{L}\{f_2(t)\} = \frac{1}{s+1}\)

So if we want to talk about the inverse Laplace transform of \(\frac{1}{s+1}\) we want to know what function has Laplace transform \(\frac{1}{s+1}\). As we can see there can be more than one answer but, unless there is a compelling reason to do otherwise, we will always assume that the inverse Laplace transform is the continuous answer and we would say:

\[\mathcal{L}^{-1}\left\{\frac{1}{s+1}\right\} = e^{-t}\]

Once we know the Laplace transform we can put it in a table. See the text or the end of these notes for an incomplete list of Laplace transform pairs. If you look at row 4 of Table 1 you find that:

\[\mathcal{L}\{e^{\alpha t} \} =\frac{1}{s-\alpha} \qquad \text{and} \qquad \mathcal{L}^{-1}\left\{\frac{1}{s-\alpha }\right\} = e^{\alpha t}\]

Solution:

\[\begin{align*} f(t) & = \mathcal{L}^{-1}\{F(s) \}\\ & = \mathcal{L}^{-1}\left\{\frac{3}{s+2}\right\} + \mathcal{L}^{-1}\left\{\frac{5}{s-2}\right\}\\ & = 3\mathcal{L}^{-1}\left\{\frac{1}{s+2}\right\} + 5\mathcal{L}^{-1}\left\{\frac{1}{s-2}\right\}\\ & = 3e^{-2 t} + 5e^{2 t} \end{align*}\]

So \(\boxed{f(t) = 3e^{-2 t} + 5e^{2 t}}\)

5.2 Laplace Transform Pairs

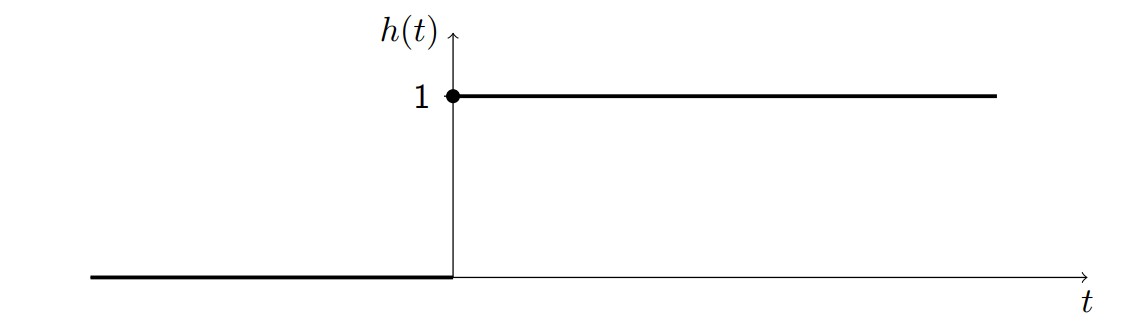

Heaviside Step Functions

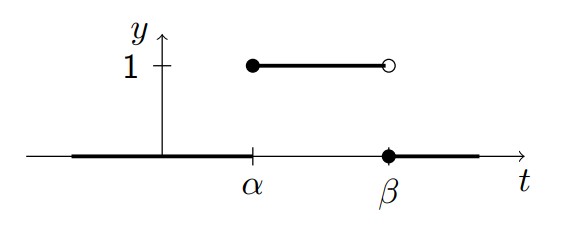

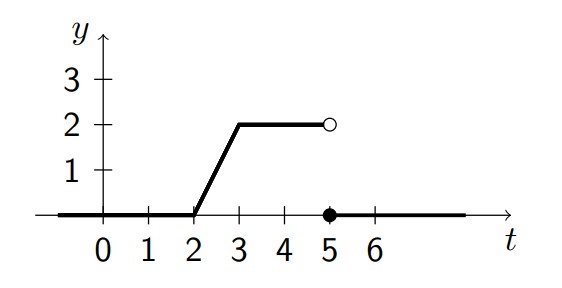

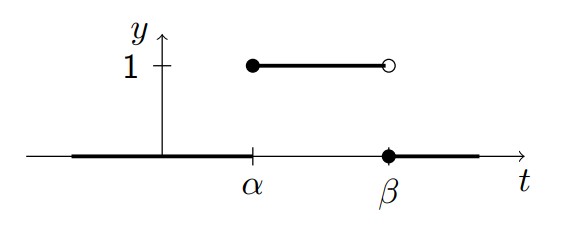

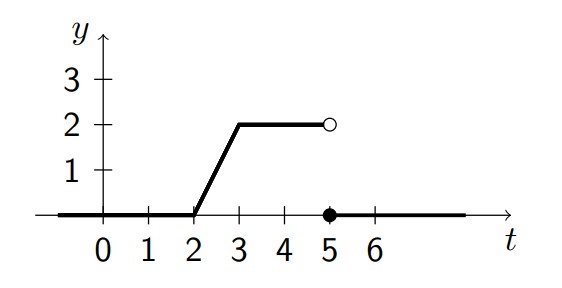

The unit step function or Heaviside step function is defined as follows:

\[h(t) = \begin{cases} 1 & t \geq 0\\ 0 & t<0 \end{cases}\]

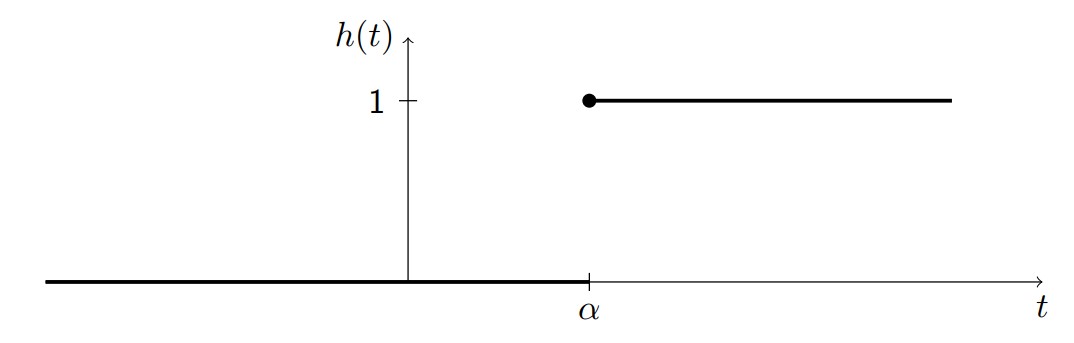

Shifted by \(\alpha\):

\[h(t-\alpha) = \begin{cases} 1 & t \geq \alpha\\ 0 & t<\alpha \end{cases}\]

Solution:

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L}\{h(t)\} &= \int_0^\infty h(t)e^{-st} dt = \int_0^\infty e^{-st} dt = -\frac{1}{s} \left[e^{-st} \right]_0^\infty\\ \mathcal{L}\{h(t)\} &= \frac{1}{s}, \quad s>0 \end{align*}\]

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L}\{h(t-\alpha)\} &= \int_0^\infty h(t-\alpha)e^{-st} dt = \int_\alpha^\infty (1)e^{-st} dt = -\frac{1}{s} \left[e^{-st} \right]_\alpha^\infty\\ &= -\frac{1}{s} \left[0 - e^{-\alpha s} \right]\\ \mathcal{L}\{h(t-\alpha)\} &= \frac{1}{s} e^{-\alpha s}, \quad s>\alpha \end{align*}\]

What is \(\mathcal{L}(1)\)?

Laplace Transform Tables

Shift Theorems

First Shift Theorem (s-shift): \(\mathcal{L}\{e^{\alpha t} f(t)\} =F(s-\alpha)\)

where \(\mathcal{L}\{f(t)\} = F(s)\) (See #9 on Table 1)

Second Shift Theorem (t-shift): \(\mathcal{L}\{f(t-\alpha) h(t-\alpha)\} = e^{-\alpha s} F(s)\)

Inverse Laplace Transforms

Laplace Transforms of Derivatives

\(\mathcal{L}\{ f'(t) \} = s\mathcal{L}\{f(t)\}-f(0) = sF(s) - f(0)\)

\(\mathcal{L}\{ f''(t) \} = s^2F(s) - sf(0) - f'(0)\)

\(\mathcal{L}\left\{ \int_0^t f(u) du \right\} = \frac{\mathcal{L}\{f(t)\}}{s} = \frac{F(s)}{s}\)

5.3 The Method of Partial Fractions

| Type | Denominator | Partial Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| Linear | \((s+a)\) | \(\frac{A}{s+a}\) |

| Repeated Linear | \((s+a)^n\) | \(\frac{A_1}{s+a} + \frac{A_2}{(s+a)^2} + \cdots +\frac{A_n}{(s+a)^n}\) |

| Quadratic | \(s^2+as +b\) | \(\frac{A_1 s + A_2}{s^2+as +b}\) |

| Repeated Quadratic | \((s^2+as +b)^2\) | \(\frac{A_1 s + A_2}{s^2+as +b}+\frac{A_3 s + A_4}{(s^2+as +b)^2}\) |

Note:

\[\mathcal{L}\left\{e^{\alpha t} t^n \right\} = \frac{n!}{(s-\alpha)^{n+1}}\]

\[\mathcal{L}\left\{e^{\alpha t} \sin \omega t \right\} = \frac{\omega}{(s-\alpha)^2 +\omega^2}\]

\[\mathcal{L}\left\{e^{\alpha t} \cos \omega t \right\} = \frac{s-\alpha}{(s-\alpha)^2 +\omega^2}\]

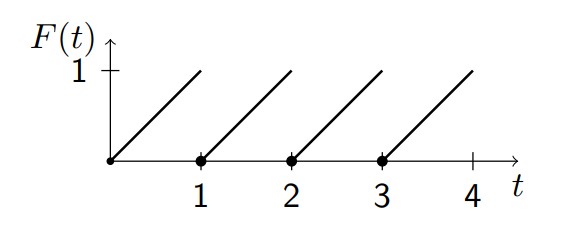

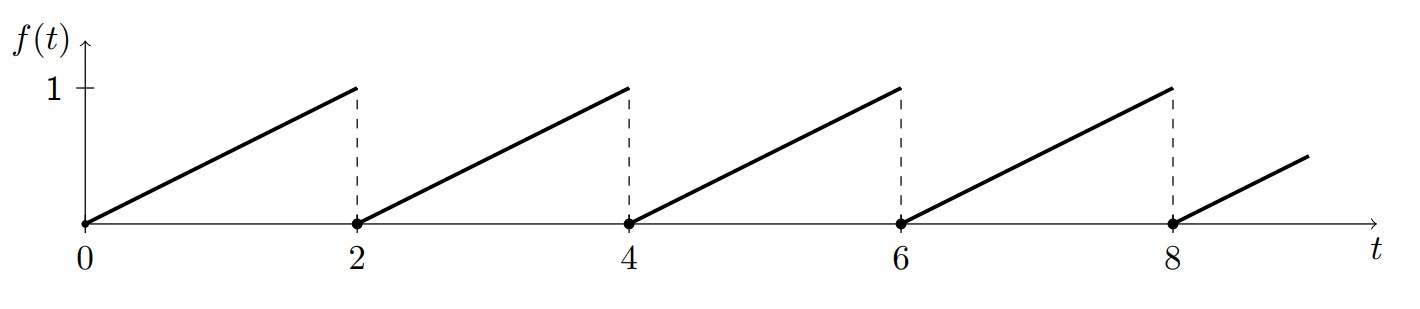

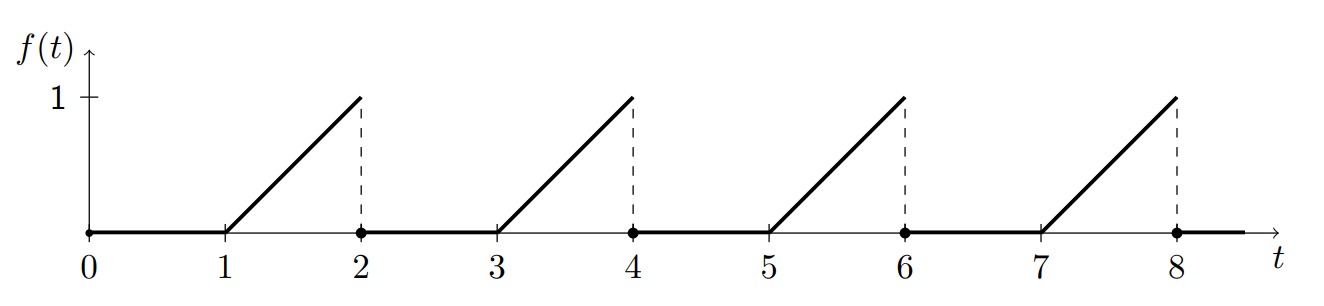

5.4 Laplace Transforms of Periodic Functions and System Transfer Functions

Periodic Functions

System Transfer Functions

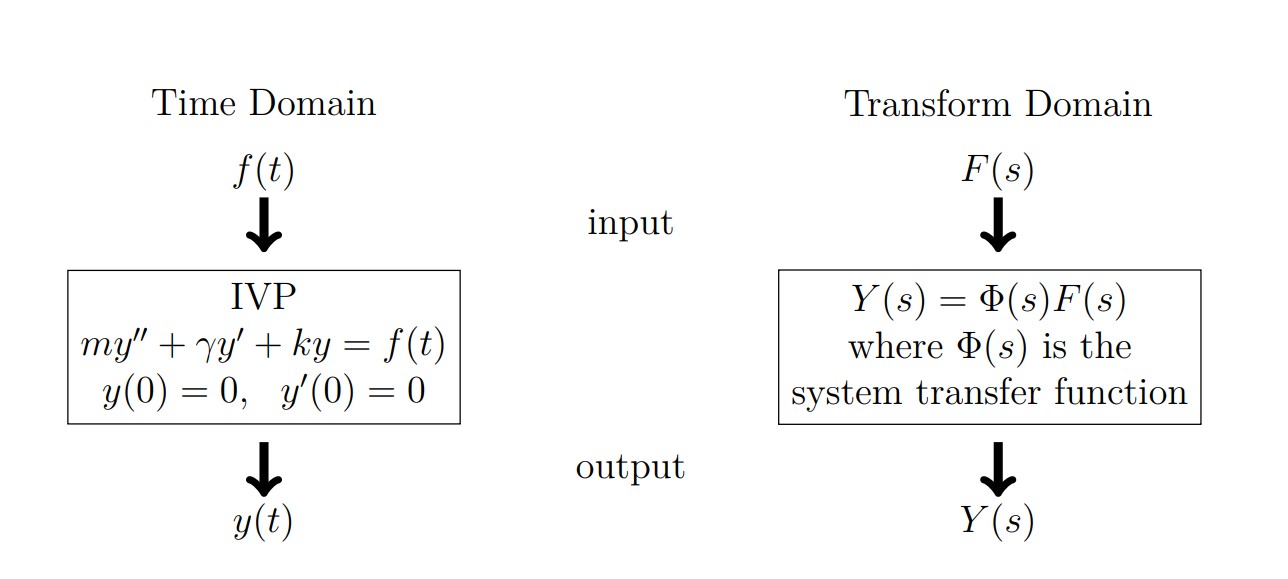

Consider the spring mass damper system we studied in Chapter 3. Given a mass \(m\), a damper with damping coefficient \(\gamma\) and a spring with spring constant \(k\) then the system from equilibrium can be modeled by the differential equation:

\[my''+\gamma y' +ky =f(t), \quad t\geq 0, \qquad y(0)=0, \quad y'(0) = 0\]

where \(f(t)\) is some external force.

We can solve this using the techniques from chapter 3 or we can solve it using Laplace transforms by using:

\(\mathcal{L}\{ g'(t) \} = sG(s) -g(0)\)

\(\mathcal{L}\{ g''(t) \} = s^2G(s) -sg(0)-g'(0)\)

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L}\{my''+\gamma y' +ky \} &= \mathcal{L}\{f(t) \}\\ m(s^2Y(s)) + \gamma (sY(s)) +kY(s) &= F(s)\\ Y(s) &= \frac{1}{ms^2 + \gamma s + k} F(s) \end{align*}\]

We can think of \(\dfrac{1}{ms^2 + \gamma s + k}\) as a single item and call it \(\Phi(s) = \dfrac{1}{ms^2 + \gamma s + k}\). Then our equation in the transform domain is simply:

\[Y(s) = \Phi(s) F(s)\]

where \(\Phi(s)\) can be found from knowing the input \(F(s)\) and the output \(Y(s)\) and nothing else.

\[\Phi(s) = \frac{Y(s)}{F(s)} \tag{5.4}\]

\(\Phi(s)\) is called the system transfer function.

Figure 5.1: Two ways to solve a mechanical system. In the time domain or the Laplace domain.

5.6 Convolution

Recall: In Section 5.4 we looked at system transfer functions as a way of predicting behavior. The system transfer function for a known input \(f(t)\) and known output \(y(t)\) is given by:

\[\Phi(s) = \frac{Y(s)}{F(s)}\]

We used this function to answer the question, “what is the new output \(\hat{y}(t)\) for some new input \(\hat{f}(t)\)?”

\[\hat{Y}(s) = \Phi(s) \hat{F}(s)\]

so the solution requires us to inverse Laplace transform a product:

\[\hat{y}(t) = \mathcal{L}^{-1} \{\hat{Y}(s) \}=\mathcal{L}^{-1} \{ \Phi(s) \hat{F}(s) \}\]

To solve this problem without needing to compute the inverse Laplace transform we have the convolution integral:

5.7 The Delta Function and Impulse Response

We will define the delta function \(\delta(t)\) to be the function with the following property:

\[\int_a^a \delta(t) dt = 1\]

We can do this by using the impulse function:

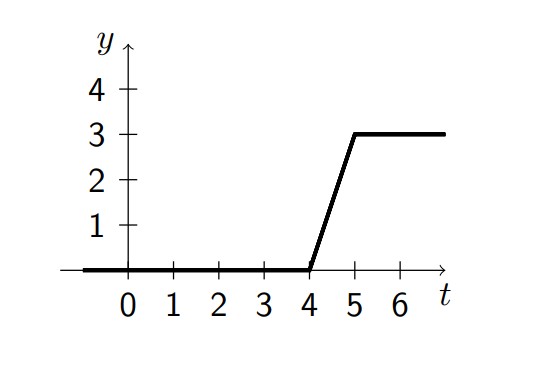

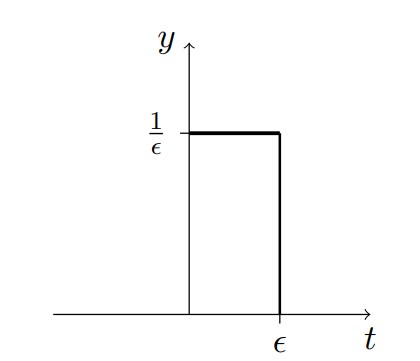

\[P_{\epsilon}(t) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{\epsilon}, & 0 \leq t <\epsilon\\ 0, & \epsilon \leq t <\infty \end{cases}\]

drawn below.

We can think of the delta function as the limit of the impulse function: \(\delta(t) = \lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0} P_{\epsilon}(t)\). This is not the formal definition but it is close enough to get an idea of what is happening. The Laplace transform of the delta function (row #27 in Table 1) is:

\[\mathcal{L}\{\delta(t-\alpha) \} = e^{-\alpha s}\]